What does a word have in common with a famous villain?

I was reading Bram Stoker’s Dracula in high school. At the time, I wanted to improve my English by reading a proper classic, and what better book to pick than the one that created the first vampire?

You see, I had just finished watching Hellsing Ultimate. I think that’s what led me to the book. There was a scene in it where a character actually refers to the book by name. She tells the soldiers to read Bram Stoker for more information on vampires… and I followed through with that advice 🙂

(Years later, hearing that ‘‘Burammu Tsouka’’ still makes me shiver.)

Trying to Read Dracula as a 15 y.o.

As expected, the book was really hard for me to understand. In every paragraph I encountered a word I never heard of before. It was real work. I could understand it really well only after putting in enough effort. My method was to first look at the dictionary to read the definition and some example sentences. Then i would go back to the book knowing the word, and try to put it all together.

I had to do this for many paragraphs, but given enough effort, there was nothing in the book that i wouldn’t be able to decipher sooner or later.

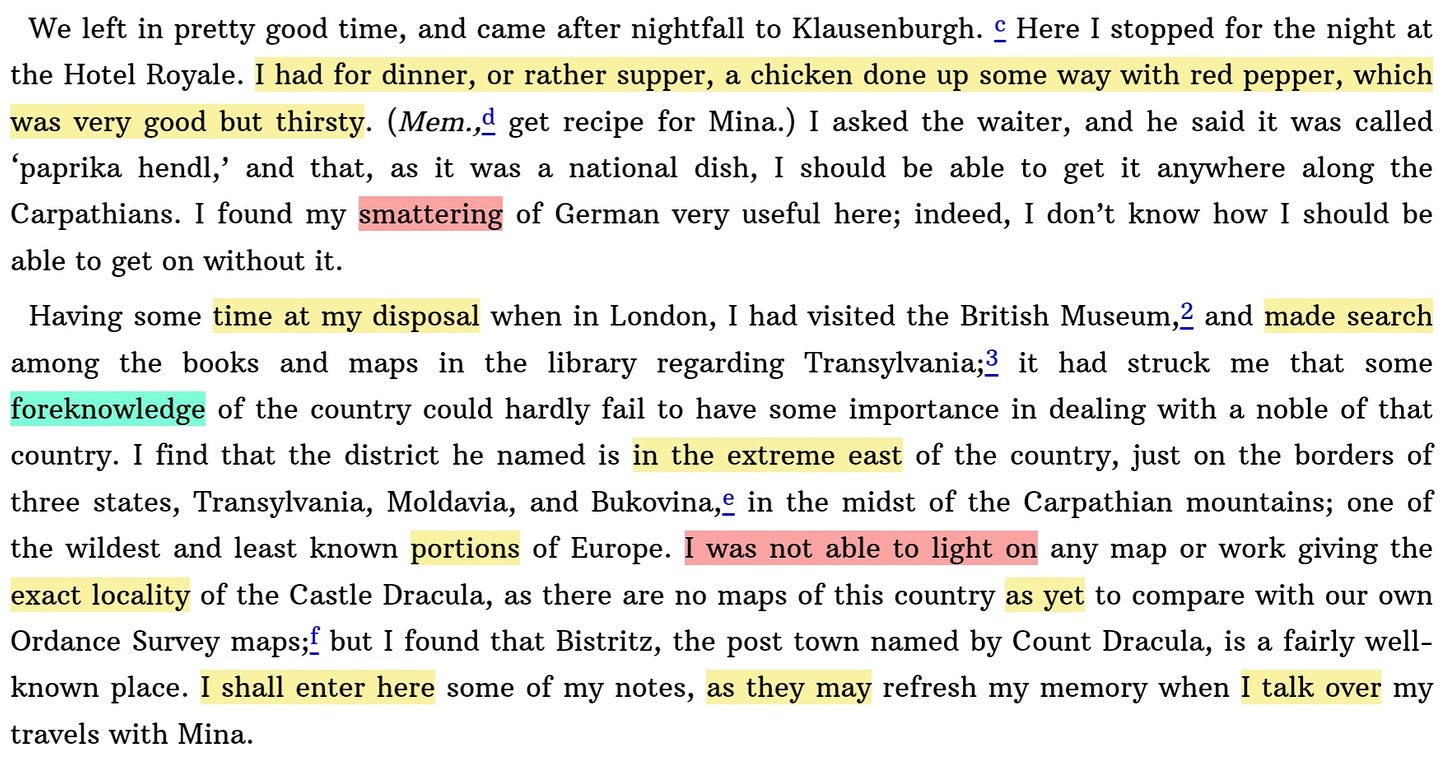

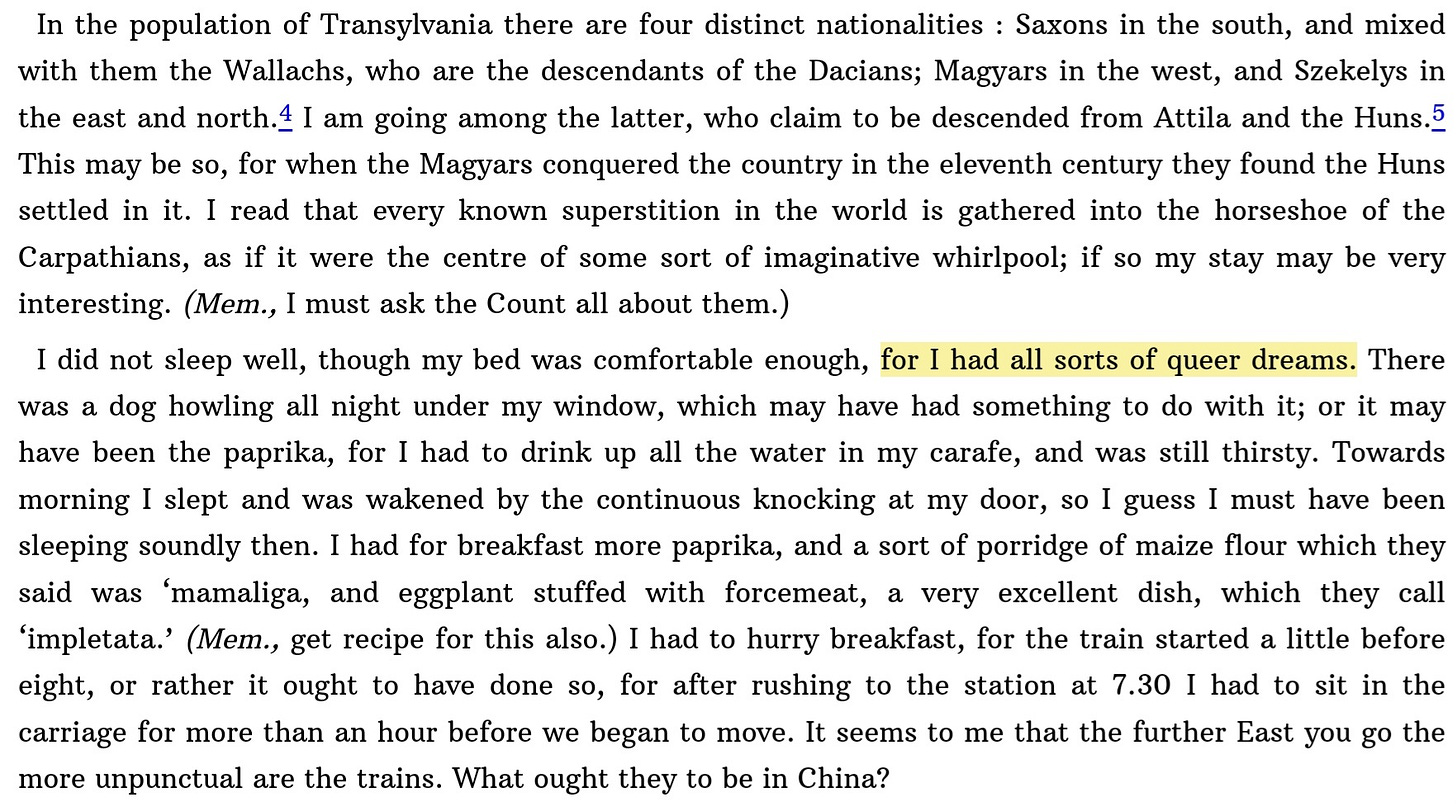

For context, here are some paragraphs from the book. I highlighted some sentences and words that strike me as being outdated.

(Really though, who doesn’t have a queer dream from time to time?)

There were some words I had a really hard time with though. I usually found that some words used by Stoker didn’t exist at all in dictionaries. As I understood, these were relics of the past, words from late 19th century Britain that somehow transformed or got lost since then.

One of these words was Backsheesh.

In Search of a Word: Backsheesh

In chapter 7 of the book, in the captain’s logbooks describing their passage through the Bosporus, it is said that they gave backsheesh to the customs officers. What could this word mean? I couldn’t find it in my dictionary.

After some time googling the word ”Backsheesh”, i finally gave up and went back to the book. There was a commentator’s notes at the end of the book, explaining some archaic words and phrases used throughout the story. There it was said that the word meant ”tip or bribe”. I wasn’t satisfied with that though, because for all my googling of different spellings of this archiac word, I hadn’t been able to find a single dictionary entry for backsheesh.

I gave up and continued reading where i left off, accepting that this was just not something I would be able to understand. I still used the meaning from the appendix in context to understand what was going on. The sailors were giving the port officials a ”tip or bribe” to pass through. They must’ve been bribing them so they wouldn’t search their ship, and find the encased Count Dracula sleeping in a coffin inside the lower compartment…. Wait a second… Could it be? The word Back-sheesh… Is it actually Bahşiş?!

It suddenly dawned on me, that the word I’d been staring at for the last 20 minutes was a word i knew all along !

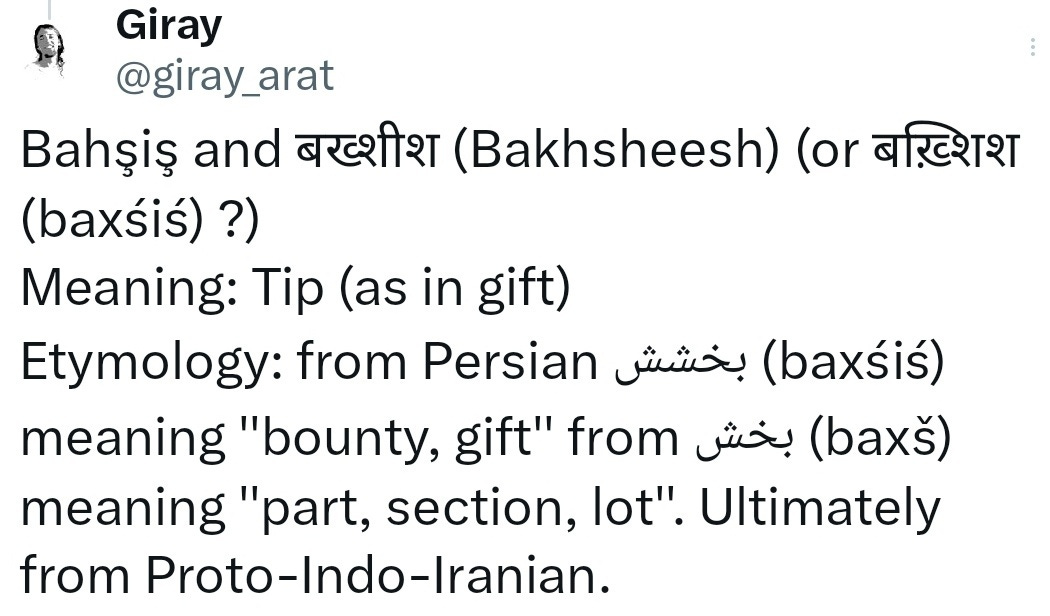

Bahşiş means ”tip” in Turkish. It’s a word we use all the time. This must have been an archaic transcription of it. Backsheesh!

The Turkish word still didn’t fit the context exactly though. Because you wouldn’t tip an official. I would never give a government worker a ”bahşiş”. If i did give a govt official money, it would be considered a ”rüşvet”, which is a bribe.

Since Backsheesh doesn’t mean bribe, but the book calls it that, I thought it must have been a clever usage by the port officials of 1800s Istanbul, who decided to refer to a bribe as a tip. But since Bram Stoker didn’t actually travel to Istanbul or even Eastern Europe, i can’t see how he could adopt the usage from real people living there. Unless, it was intentional… Did he really know the meanings of both words ”rüşvet” and ”bribe”, and created a beautiful wordplay that none of his readers could understand?

In another explanation, he could have just been talking about a toll. Maybe, somehow, he read a book about Eastern Europe that said the word Backsheesh meant a toll. In that case, the word ”bahşiş” must have changed meaning since then. Through the natural evolution of languages.

I didn’t inquire any further though. Maybe I didn’t know how… In any case, I was satisfied with what i learned and returned to read the rest of story.

My First Lingusitics ‘‘Eureka!’’

Discovering the meaning of Backsheesh felt great at the time. I was able to find the meaning of a word that no dictionary had, just by knowing another language, and spending enough time pondering meanings. I think that’s how actual linguists operate. Knowing the basic mechanics of many languages around the world, they can infer the meaning or origins of unknown word by recognizing the underlying structure.

I was around 14 at the time and, this was magic to me. It was like a linguistics ”eureka!” moment. It felt this way especially because i didn’t need to get help from any teachers or adults to do it. It was just all me, messing around with words from a book, going on a journey, alone in my room.

Backsheesh is in Hindi Too!

This week I joined an event in Turkey where I met someone who speaks Hindi. To my surprise, she was able to recognize some Turkish words i used from Hindi. I wrote about it on Twitter and other people contributed with words they recognized. And backsheesh was one of them!

When i looked the hindi version up, i found that it means exactly the same thing as it does in Turkish. It means tips. Turns out almost all of the words Hindi and Turkish have in common are of Persian origin.

Empires in Motion: the Journey of Backsheesh

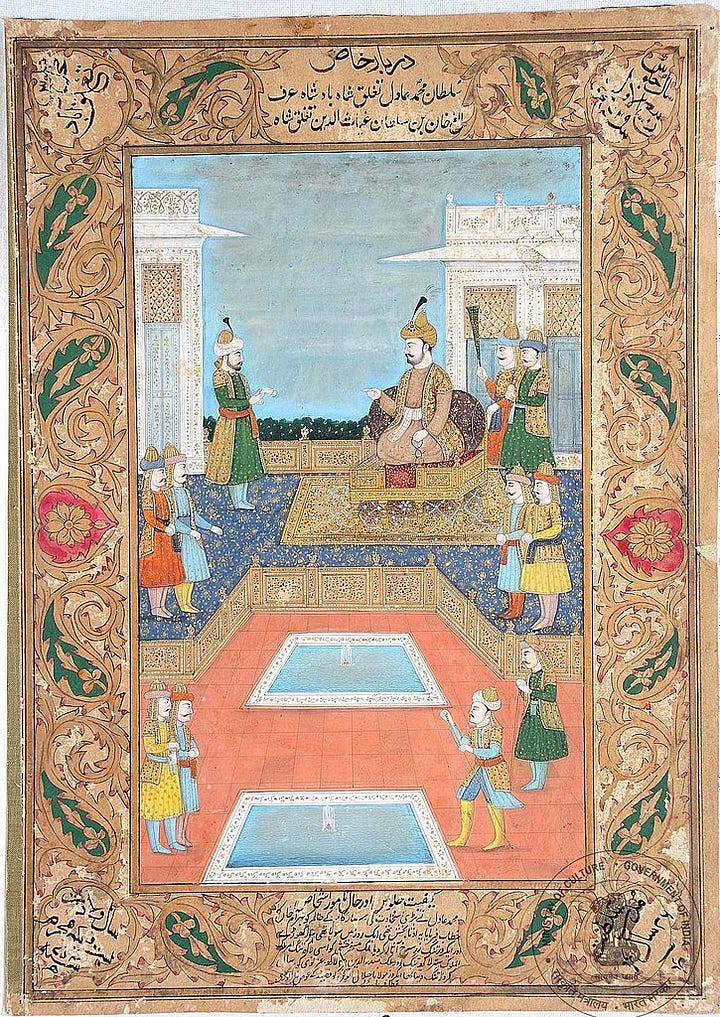

For Hindi, Persian words were brought by Turko-Persian rulers conquering their way into India. Persified Turkic and Turkic-Mongolic invasions into Northern India created multiple dynasties, in which the muslim ruling class spoke Persian, A.K.A. Farsi, which was considered the language of international relations and of the elite.

These dynasties introduced strong Persian influence into the local culture. For example, the Mughal Empire (1526-1857) declared Persian as the official language of their state. As languages changed and new ones developed, many Persian words made their way into local dialects, which ultimately stemmed from Sanskrit. As a result of centuries of co-habitation, Hindi now has many words of Persian origin.

left: Painting depicting Muhammad bin Tugluq, Prince of the Tughluq (or Tughluk) Dynasty (1325 – 1351), ruler of the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526)

right: Mughal era Taj Mahal (built 1600s)

The Turkish Leg

You know where else was conquered by (semi-Persianified) Turkic peoples? Turkey.

It was the Oghuz Khanates, who conquered their way deep into Anatolia, and resulted in a sucession of devlets (some of which would become continent-spanning empires), who brought the Persian language into modern day Turkish.

The first Empire that caught a foothold in Anatolia was the Seljuks. They reigned from 1037 to 1197. They used Persian as the language of the high court, while being Turkic themselves. At its highest point, the Seljuk Empire included Persia, and their area looked like this:

(Seljuk empire circa 1090, the dashed area is territory belonging to a sibling rival state, ”the Seljuk Empire of Rome”)

The successor Ottoman Empire replaced Persian with Turkish, and used it as the basis of their lingua franca ”Lisân-ı Osmânî”. Ottoman Turkish, ultimately drawing from its predecessors, had a lot of loan words from Persian. Meanwhile, Persian continued to be the language of the elite. Some people in the court spoke all of the three languages deemed important for Ottomans at the time: Arabic, Persian and Turkish.

Ottoman Empire lasted almost 700 years, from 1299 to 1922. At the time Dracula was passing through the Bosporus, the Ottoman state was still alive and kicking. The officials at the port were Ottoman, and you had to give them a Backsheesh to pass through.

Bosphorus, Ivan Aivazovsky, 1878

Long Time No See

Today, when I look up the word Baksheesh in English dictionaries on the internet, i can find it easily. Back then I was using a print Oxford Dictionary, which didn’t have it. Even the digital Oxford dictionary has it now. It says it means ”a gift to poor people, or given to somebody to thank them or to persuade them to help you.” The meaning is still a bit conflicted, somehow the word got mixed up with bribery as it passed on to English.

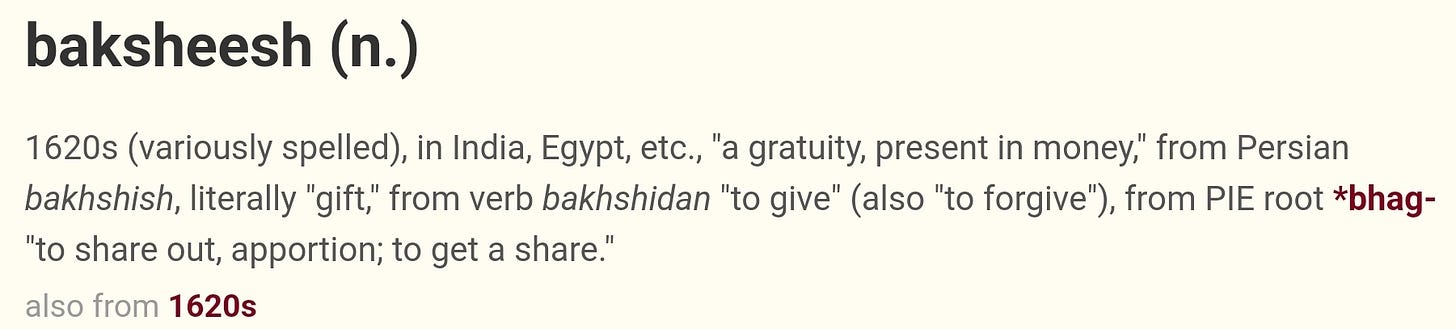

The passage of the word into English seems to be properly recorded too. It has almost the correct meaning in the etymological dictionary: ”a gratuity”; but hints at the future meaning of bribery with: ”a present in money”. Etymonline (my source) doesn’t tell the first recorded usage (it should), but it says it entered into English in the 1620s. Makes sense. This was already a maritime age for English speakers and North Europeans. Ottoman Empire had been controlling the Bosporus for 200 years at that point. It is understandable that this word somehow got carried into English by maritime trade with the Turks, and thus was mixed in with the hidden meaning of bribery.

Maritime Trade of Cultural Goods

Sailing always widened humanity’s horizons. Language and culture flowed in, riding on the ships. Ports were a hotspot where all the nations of the world came together.

Just like how the Count was carried all the way from strange Transylvania to London through the Turkish Bosporus channel, gateway between the mystical East and the familiar West…

The word Backsheesh travelled all the way from Persia, hitching a ride on the tongues of Turkic peoples, and popped up in a 1897 English novel called Dracula.